|

GBNI01 |

GBNI02 |

GBNI03 |

|

|

||

|

GBNI04 |

GBNI05 |

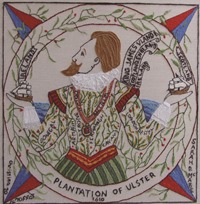

The ancient cultural and historical links between Scotland and Ireland are well known (see Republic of Ireland), but whilst a Gaelic culture links Ireland to the Highlands, there is a particular legacy binding Northern Ireland to the Scottish Lowlands. The story predates the twentieth century partition of Ireland, and relates to a period of deliberate Scottish settlement in the region of Ulster (which now incorporates part of the Irish Republic as well as Northern Ireland). In the reign of King James VI & I, the newly united Crown sponsored an official programme of colonisation which confiscated lands from native Irish landowners (primarily Catholic) and distributed them to (predominately Protestant) settlers from both England and Scotland. Many of those who initially lost their lands were the leaders of the recently defeated opposition to English (and now Scots) control of Ireland.

Eastern areas of Ulster also saw a considerable amount of private plantation, notably those founded by Sir Hugh Montgomery and Sir James Hamilton. The former (right) developed the harbour at Donaghadee to better facilitate migration, primarily from Ayrshire and south-west Scotland into Down and Antrim, and founded a ‘great school’ at Newtownards. Although one of the primary aims of the plantation was to establish a loyal Protestant powerbase in Ireland, it was not always just the Irish that the programme sought to tame. Border names like Elliot, Hume and Armstrong can be found in Ulster today, recalling King James’ attempts to break the power of the Border Reivers after the union of the crowns. Banished from the traditional lands, many reivers crossed the sea and established themselves in Northern Ireland.

Life was not easy for the Ulster-Scots settlers. They faced resentment from the native Irish, their Catholic neighbours, and could be penalised unless they subscribed to the official Anglican Church of Ireland – something many of the Presbyterian Scots would not do. Resentment and hostility came to a head in the 1640s when bloody war broke out across Ireland. A large Covenanter army arrived from Scotland to help protect the Ulster-Scots, whilst civil war raged for a decade across the whole of the British Isles. After the collapse of the Royalist cause in England, Oliver Cromwell brought a brutal end to the conflict in Ireland prior to his invasion of Scotland, and with the peace came fresh confiscations of Catholic land to repair some of the damage done to the earlier settlements. By the end of the seventeenth century the Protestants had a numerical supremacy in Ulster, helped by continued immigration, but the Presbyterians amongst them still faced sufficient restrictions over the next century to encourage many to move further afield, especially to the new world.

The legacy of the Ulster Scots lives on of course, in the cultural heritage and even the dialect of parts of Northern Ireland.

.JPG)